I cry. A lot. Well, not everyday. And not to the point where I need to be sedated or dragged to a special ward. But I do cry on the regular. The water works can start anywhere, anytime, from watching a cute kitten video or from watching Rachel and Ross *finally* kissing on Friends — even if I’ve seen that episode a million times. It doesn’t matter. There are always tears lingering on the surface. I blame my Pisces rising. Or some unresolved childhood trauma. Who knows.

Anyway. Cry baby. That’s me. At least that’s what my nickname was when I was six years old and I guess it’s stuck. When I was 22, I was in acting class and I could cry at the drop of a hat. My teacher marvelled at how easy it was for me to cry. But he didn’t really chalk it up to talent so much as calling me a Highly Sensitive Person. It was the first time I heard the term, and after buying the book by Elaine Aron, my intense sensitivity and knee-jerk crying made sense (among other things, like hating large crowds and loud noises).

So yes, I cry. A lot. And I wrote about it for Ravishly back in 2015. What I always find remarkable (and kind of cool and special) about going back in time and revisiting old essays of mine is being reminded of things about my life that I totally forgot about. There are a few instances in the essay below that I was gently reminded of, and I have a lot of compassion for myself then, and now, and my capacity to hold all those things. all those feelings EVERYDAY.

If you’re a cry baby, or a highly sensitive person, you’re not alone. And I think it’s a very special quality to feel so much and so deeply for the world around you. We need more feelings. We need more people who can feel those feelings and express them. We need more sensitivity and empathy. We need more cry babies.

Here’s the essay.

The Trials And Tribulations Of A Cry Baby

This summer, upon my arrival at my local birth control clinic, the receptionist informed me that I had misread the hours of operation online because the clinic had just closed ten minutes beforehand. I didn’t say, “Oh, that’s too bad,” and leave. Nor did I calmly say, “But I’m only ten minutes late. Don’t you think the doctor could see me?”

Nope. Instead, I cried. I cried because I was frustrated at myself. I cried because I didn’t have a backup birth control and because my hormones get kinda hairy, and fuck, I was just ten minutes late! “Let me see what I can do,” the receptionist told me between sniffles, and I was soon brought in. Afterwards, on my way out, she said to me, “We’ve all been there.”

I‘ve always cried a lot. When I was in the first grade, I was nicknamed “Cry Baby” by my peers. I cried when I was picked last for tag at recess. Because I cried while watching “Benji” when the helicopter left him stranded on the mountain (I cried so much I had to leave the classroom). I cried if someone talked back to me. I cried if I talked back to someone. Sometimes I didn’t even know why I cried. I cried and cried because I had so many feelings going on, and I just didn’t know how to handle them.

“You cry too much,” a girl named Stephanie told me at summer camp after I burst into tears after her comment that there was something “wrong” with me because, at thirteen, I hadn’t French kissed a boy before. “You’re way emotional.”

Of course, her caustic remark only caused the tears to keep on gushing. I was ashamed of my tears. I wanted to be like the other kids who seemed to go with the flow more, who seemed to give zero fucks about anything. The Stephanies of the world who spoke up, said whatever was on their mind, and left the tent with the flip of her hair (to probably go French kiss some boys).

I kept a lid on the tears during high school. It’s not that I wasn’t being myself, but, somehow, through studying for SATS and applying to university and dreaming of living in New York—by having a focused goal—life didn’t seem as overwhelming to me. I liked being in control of my feelings. I was no longer at their mercy, which meant I wasn’t being ostracized because of them. I saved my crying for the times when I was rejected by a crush or when my best friend almost transferred to a new school. But I was far from being a Stephanie; the tears were still there, albeit, bubbling near the surface. The truth was I had only plugged a temporary hole in a very leaky dam.

I was twenty-two when I exploded. I had recently graduated from NYU and wondering what to do with, well, the rest of forever. Life was scattered, and blurry.

Everything about my world affected me much more deeply than I had ever experienced before and, so, I cried. A lot. It was around this time when I finally discovered the reason behind the tears that had plagued me throughout my life. My acting teacher suggested I read a book called, “The Highly Sensitive Person,” by Dr. Elaine Aron. It changed my life.

For the first time I realized why I am the way I am. Why my emotions are so vivid; why I pick up on other people’s energy so readily; why watching heavily emotional—or violent—movies affects me so viscerally, or why noises just bother the shit out of me sometimes. At last, I understood why I cry for apparently no reason; it was simply because, I was built this way. It explained so much. Like, when I burst into tears after having sex with my first-ever boyfriend because I was falling in love. At first, that scared the shit out of him (I mean, who could blame him?). But after I told him how I was feeling in order to explain the tears (and to reassure him it wasn’t due to his performance, or lack thereof), we professed our love to each other.

Finally, I didn’t feel “out of touch” with the rest of the world anymore, and more importantly, I was feeling “in touch” with myself.

As I continued to embrace my own sensitivity, it became less embarrassing and less shameful to cry whenever my emotions overtook the motherboard. This explains why I’ve cried in many places, many public places. Take the subway, for instance. I’ve cried on subways anywhere from Toronto to New York for numerous reasons: I bombed an interview with a top talent agency, I was fired as a theater usher, I was on my way to a party that I really didn’t want to go to or my sweater was super itchy and bugging the shit out of me. Whenever these crying circumstances occurred, I’d get a sympathetic head nod, a curious glance from the top of a newspaper, the occasional offering of a tissue, sometimes a scowl.

A few years back, I was on the A train in New York. It was a Monday morning and I was on my way to “officially” break up with my boyfriend (post-sex crying boyfriend) at a Starbucks. A garbage bag was at my feet. The bag was filled with things my ex had left at my apartment: a toothbrush, a ratty T-shirt, a couple of Richard Ford books.

I had placed them in the garbage bag because I was trying to make the point of: “You’re garbage to me now!” But he wasn’t. I still loved him, and I was sad, and so the tears that I had promised not to shed, came flowing out like an overworked faucet. A homeless woman was sitting kitty corner from me. She watched me for a few minutes as I failed to compose myself.

“You OK?” She finally asked.

“Yeah…” I hiccuped. “I will be.”

“You just let it out, honey,” she said to me. “You just let it out.”

Over time, I’ve realized that when I am more accepting of who I am and of what I am experiencing in the present moment, my tears not only help me connect with myself, but also connect me to the people around me—even if the end result isn’t the most desirable.

After embarking upon a romantic European vacation with my boyfriend this past summer, I couldn’t stop crying during our last morning together. But I didn’t want to expose my tears to him. We hadn’t been dating for too long and I was surprised, and even a little embarrassed, on how much I felt. I came up with every excuse in the book to explain the waterworks. “I got shampoo in my eye!” “I think I caught your cold!” “Boy, I miss my cat!” I even wore my sunglasses inside of his apartment. “The sun’s getting in my eyes,” I told him. I finally came clean to him at the airport when he dropped me off.

“I’m going to miss you,” I said, finally taking off my glasses and rubbing my eyes. “I’m sorry for crying,” It was the first time in a long time I had apologized for crying, and it felt like a betrayal.

“It’s okay,” he said. “You can cry.”

When we eventually broke up, he said to me, oh-so-bittersweetly: “I didn’t know how you felt about me until you cried that morning. I’ve never gotten as close to anyone as I’ve gotten to you when we were at the airport.”

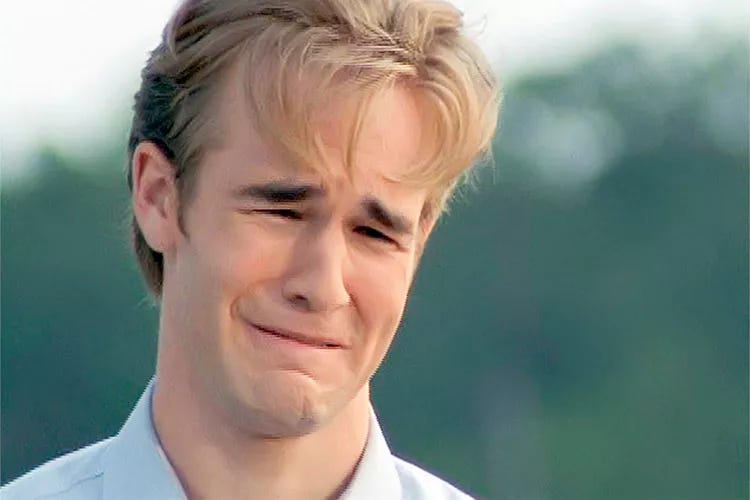

If I had a nickel for each time an emotionally unavailable love interest told me I made them “feel something” because of my shameless crying in front of them ... I’d be, well, like only 25 cents richer, but here’s my point: Being in touch with my own feelings, and so unabashedly so (at this point, I should mention that I am an extremely ugly-James-Van-der-Beek crier) has permitted others to soften, to empathize, to explore their own vulnerability and humanness.

For much of my life, I was ashamed to feel all the feelings and express them; I thought there was something wrong with me. But as life has proven to me over and over again, we’ve all felt all the feelings at some point in time. And, yes, we’ve all cried.

I’d like to say that after he dropped me off at the airport that day, I stopped crying. I didn’t. I cried while I was at the ticket kiosk, self-checking myself in. I cried while I dropped off my baggage.

“Are you all right?” The attendant asked me.

I nodded.

“You sure?”

“I’m sure,” I managed to say before proceeding to the security line, which was where I started to cry the hardest. I suddenly felt a tap on my arm and came face-to-face with a tough-looking and very tall TSA agent. Oh shit, I thought. I’m causing a scene.

He’s going to take me into a backroom and—

“Is everything okay, ma’am?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said quickly, my heart pounding hard against my chest.

“You sure? Because you look very upset.”

“I-I just said good bye to someone who I really care about.”

“Oh yeah?” The TSA agent’s demeanor lifted. “Do you need anything? Do you want to go in front of the line or something?” If it hadn’t been for the scowling couple behind me, I would have (and, frankly, should have) but instead I said, “No, but thank you. I’ll be all right.”

“You take care, ma’am,” he said. “You take care.”

You can read the original printed essay here.